Asbestos exposure.

Millions upon millions of Americans have been exposed to asbestos, a cheap and plentiful mineral known to cause mesothelioma cancer and other diseases.

Knowledge is power—and for that reason gaining knowledge about asbestos exposure is an important step in becoming properly equipped to fight mesothelioma.

And the ability to fight mesothelima is essential to hope for survival.

The Truth About Asbestos Exposure was Long Hidden

Health professionals have understood for a long time that asbestos causes cancer as well as several non-cancer illnesses.

Exposure to asbestos can cause:

- Mesothelioma

- Asbestosis

- Lung Cancer

- Fluid in the Lung Cavity

- Chronic Obsctructive

Medical investigations into asbestos as a cancer-causing agent date back to the early part of the 20th Century.

The findings of those investigations were shocking. However, corporate interests managed to hide the truth about asbestos exposure even after the results of the investigations were published.

It so happened that asbestos in those days was big business. Asbestos was seemingly everywhere and in everything used by Americans at work, at home, and in their leisure activities.

Too much money was at stake to allow asbestos to become tainted in the minds of consumers and workers. Accordingly, businesses that stood to profit from asbestos and asbestos products prevented the media from talking about the dangers of this common mineral.

So, use of asbestos continued and grew until the 1960s. It was then that Big Business lost control of the narrative. News that long had been suppressed about asbestos exposure suddenly began surfacing. The nation was horrified by what it learned.

Lawmakers in Washington, D.C., responded by instituting strict controls on asbestos and on its use in products.

Later came multimillion-dollar lawsuits against the companies responsible for exposing Americans to asbestos. The lawsuits were many, as were the victories. New lawsuits keep coming even today as the cancerous effects of asbestos exposure from decades ago continue to arise.

The good news is that, between the regulations and the lawsuits, use of asbestos in the United States has plummeted. It is much less common now to encounter asbestos products, but here are a few of the places it can still happen:

Homes, offices, schools, factories, and other structures more than 50 years old.

Fix-it business sometimes work on asbestos products discovered in an attic.

This includes once-active asbestos diggings and areas where asbestos is naturally in the soil.

Companies at the Center of Asbestos Exposure

Johns-Manville Corp. was for many years in America the biggest name in asbestos.

The company was born in 1901 when enterprises owned by Henry Ward Johns and Charles B. Manville merged.

Johns’ H.W. Johns Manufacturing Company started in 1858. It was at the time headquartered in the basement of his lower Eastside New York City home.

The company’s first product was roofing shingles. Johns had figured out and patented a process for producing them more efficiently and cost-effectively. Business boomed as a result. Johns went on to develop and sell house paint, insulation, and other building materials.

Asbestos entered the picture in 1868 when Johns obtained a patent for a fireproofed and heat-shielding product.

In 1886, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Charles Manville and sons opened shop as sellers of insulation and coverings for plumbing and sewer pipes. Among his most popular wares were those made by the H.W. Johns Manufacturing Company.

So successful was Manville with the H.W. Johns Manufacturing Company line that, 15 years later, it was proposed the two concerns become one.

The post-merger company was then called Johns-Manville Corp. With Manville’s sons in key leadership positions, the product lineup grew to include other types of asbestos-containing items such as brake linings and cement. By 1923, the company’s catalogue listed over 200 different types of asbestos products.

Until 1927, Johns-Manville Corp. operated as a privately held business. That year, it went public on the strength of revenues totaling $663 million (adjusted for inflation, 1927-2020).

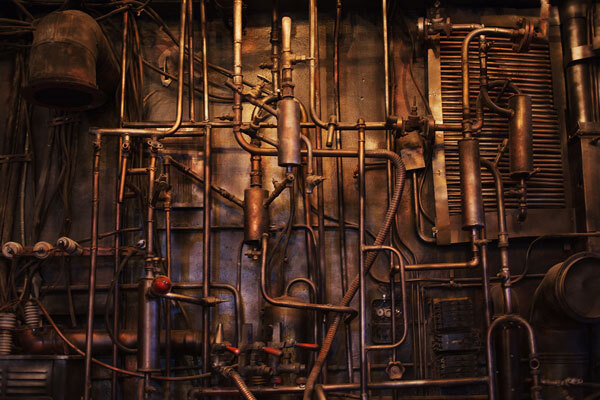

A leading customer of Johns-Manville Corp. was a company by the name of Babcock & Wilcox. If Johns-Manville Corp. was the biggest name in asbestos, Babcock & Wilcox was the biggest in boilers. Not just modest boilers, but massive ones built to power factories and ocean-going vessels as well as spin turbines to generate electricity for entire cities.

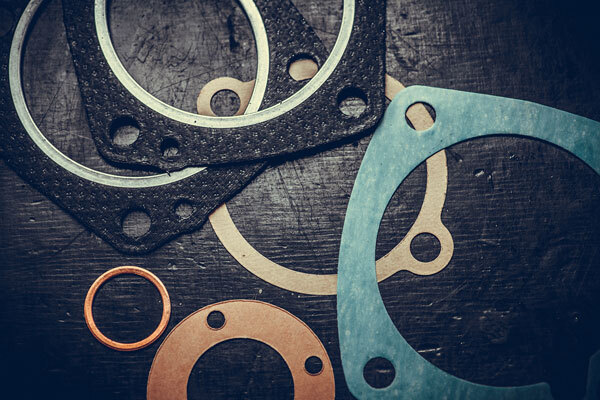

Contained within those boilers were large quantities of asbestos in the form of liners and gaskets to make sure scalding-hot heat remained inside.

Keeping heat penned up like that served three purposes. First, it made the boilers operate more efficiently. Second, it protected adjacent machinery and systems from being damaged by high temperatures that otherwise would radiate out to them. Third, it prevented the people running the boiler and adjacent equipment from sustaining injury in the form of burns.

Another big asbestos products buyer was the U.S. Navy. Starting some years prior to the Second World War, the Navy began building battleships, submarines, and everything in between with asbestos throughout. Asbestos was utilized to shield the magazine compartments where gunpowder and shells were stored. It was employed in the galleys where grease fires were a constant threat. It was put in crew quarters to give them a fighting chance at survival in the event the ship suddenly turned ablaze due to accident or attack.

Because asbestos was seen as offering so many benefits, Johns-Manville Corp., Babcock & Wilcox, the Navy, and thousands of other asbestos purchasers believed the mineral’s health risks were acceptable. Moreover, because it usually takes decades for asbestos exposure to produce mesothelioma or asbestosis, corporate officials understood that most adult asbestos-exposure victims would die of natural causes long before the onset of an asbestos illness (the average life-expectancy of Americans in the early 20th Century was around 55 years), so why worry?

There was another reason that companies believed the health dangers posed by asbestos were an acceptable risk—the law was on their side. In the 1930s and 1940s, only a few states had embraced tort law to the extent necessary for injured workers and consumers to have grounds to hold corporations liable for harms occurring long after the fact. Yet, even in those states where tort laws were available to remedy such injuries, the vast majority of potential plaintiffs were of the mindset that life is all about taking risks and, as such, it would never occur to them to sue a corporation for compensation.

Attitudes and the law began to change with the 1955 publication of a study that found a 10-times greater likelihood of developing lung cancer in people who had been exposed to asbestos over a span of 20 years.

This led to further research and other alarming insights. By the 1960s, scientists had established compelling evidence that those who had been exposed to asbestos earlier in life were at risk of serious health problems later in life.

These studies captured attention because, by this time, millions upon millions had been exposed to asbestos and people were living longer than before, making it more likely that the asbestos fibers trapped within them would have sufficient time to produce disease.

Types of Asbestos

Asbestos is a mineral found everywhere in the world. The U.S. once was a major source of it. However, today, it mainly comes from Russia and Central Asia.

Amphibole

(more toxic)

Serpentine

(less toxic)

Amphibole asbestos comes in several subtypes. They are:

- Actinolite

- Amosite

- Anthophyllite

- Crocidolite

- Tremolite

The most dangerous of these subtypes is crocidolite Serpentine asbestos comes in one main subtype, chrysotile.

Why Asbestos is Dangerous

One of the characteristics of asbestos is its structure. Seen under a microscope, amphibole asbestos appears to be made up of fiber strands. These strands are long and rough around the edges. Serpentine asbestos, on the other hand, is made up of short, smooth fibers.

The thing about the fibers of both amphibole and serpentine asbestos is that they tend to split apart rather easily. Separated strands can float in the air like dust particles. This is a big part of what makes asbestos harmful to human health.

Asbestos fibers are nearly invisible to the unaided eye. When these difficult-to-see fibers float in the air (especially in an enclosed area) there exists the possibility that a person passing by will inhale some of them. If this happens, the asbestos fibers will be carried deep into the lungs and remain trapped there.

By processes not yet fully understood, the trapped asbestos can cause healthy cells surrounding or inside the lungs to mutate into cancerous cells.

Something similar can happen to the abdomen if, instead of inhaling asbestos, the fibers are swallowed.

How Asbestos Gets Into the Air

It takes only a little jostling to send asbestos particules into the air.

A few of the ways it can happen:

- Sawing

- Hammering

- Drilling

- Tightening a screw

- Sanding or filing

- Marking it with a pen

- Bumping into it

- Disassembly/reassembly

Asbestos is placed in service

Product is cut or hit

Fibers released

Asbestos Products Come in Many Forms

Asbestos is useful for fireproofing and heat insulation. It can be applied to the outer surfaces of products as a coating or woven together with other types of fibers.

Asbestos also makes concrete, plastic and other materials stronger when mixed in as an additive ingredient.

Just some of the products asbestos in which has been used include these:

Attic Batts

Boilers

Brick Mortar

Car Brakes

Ceiling Tiles

Flooring

Furnaces

Gaskets

Gas Tanks

Girders

Paint

Patio Chairs

Pipes & Hoses

Roofing

Water Heaters

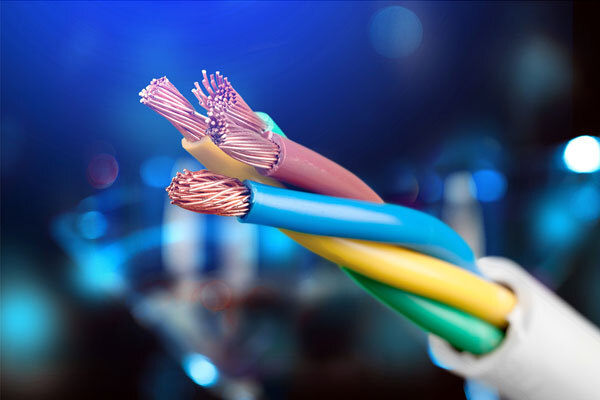

Wiring

These and countless other asbestos products did not simply make and install themselves. Humans performed that work. And as they did, asbestos fibers broke loose and floated into the air. There, they waited until a worker, a consumer, an occupant, a repair person, or just an unsuspecting passerby happened along and inhaled or swallowed.

From Asbestos Exposure Risk to Mesothelioma: A Timeline

Exposure to asbestos does not quickly produce mesothelioma or other asbestos illnesses. Asbestos has what is known as a lengthy latency. That means it might be a long time before cancer begins if you are exposed to asbestos today.

Asbestos

Exposure Occurs

Latency Period

Mesothelioma

The timeline illustration above does not necessarily mean that mesothelioma will develop 40 years after a person is exposed to asbestos. It could take 40 years, or it could take 20 or it could take 60. The point to remember is that mesothelioma, if it happens at all, will be a long time in the making.

There is much debate over how many asbestos particles one must inhale or swallow to be at risk for mesothelioma or other asbestos illnesses. Some scientists say there must a significant accumulation of fiber deposits for cancer to begin. Other scientists contend that it takes no more than a single trapped fiber to set the cellular mutation process in motion.

One thing most scientists agree on is that the risk of developing an asbestos disease rises as the number of asbestos fibers lodged within the body increases.

Compensation for Exposure to Asbestos

Merely having been exposed to asbestos is not enough to make a person eligible for compensation, whether in the form of an asbestos lawsuit (verdict or settlement) or a payout in response to a claim filing with an asbestos trust.

To receive compensation, there must also be actual (not predicted or expected) harm that can be traced back to an asbestos exposure. Also, the exposure must be the result of either willful or negligent conduct on the part of an identifiable defendant. Here, the harm is mesothelioma or other asbestos illness, and the identifiable defendant is the company (or companies) that made, distributed, sold, or installed the product containing the asbestos at the center of the exposure.

It is important to note that asbestos lawsuits are almost never open-and-shut cases. They are matters that require the knowledge and skill of an attorney or law firm focused on asbestos exposure litigation.

A lawsuit for asbestos exposure can be brought against:

- Makers for equipment containing asbestos

- Makers of equipment parts containing asbestos

- Makers of household goods or office supplies containing asbestos

- Distributors of asbestos-containing equipment or goods

- Makers, distributors, and retailers of personal protective equipment that was supposed to keep workers safe from asbestos fibers but malfunctioned and allowed those fibers to be inhaled or swallowed.

A History of Asbestos Exposure Lawsuits

The first substantial wave of lawsuits against asbestos defendants began in the early 1970s. This followed a decade of widely publicized revelations about the dangers of asbestos and about the efforts of Big Business interests to suppress warnings about those risks.

Among the initial cases to make its way to court was one in which a plaintiff who worked with asbestos-containing building materials sued the manufacturer after developing asbestosis. The year was 1972. The plaintiff’s case was argued before a jury, which was persuaded that the defendant had failed to give adequate warning that asbestos was hazardous to health. The jury awarded the plaintiff over $400,000 in inflation-adjusted damages.

Because the potential awards that plaintiffs could receive were so substantial and because there were so many potential plaintiffs, defendants realized they would be financially ruined if they did not fight these kinds of cases tooth and nail.

According to one law historian, 950 asbestos cases were brought before the federal courts alone between 1972 and 1979.

In the four years between 1980 and 1984, the federal courts reported filings of 10,000 such cases.

In the four years between 1985 and 1989, the federal courts reported asbestos case filings numbered in the range of 37,000.

In 1991, the number of asbestos case filings in all courts (federal and state courts together) stood at 115,000.

Ten years later, someone tallied all the asbestos cases that had been brought since 1972 and determined that there had been 730,000 of them against 8,400 defendants.

Of course, not all of those filings were resolved by trial. In fact, the overwhelming majority of them ended when the plaintiffs and defendants reached an out-of-court agreement to settle the matter without need of airing the facts before a jury or judge.

Today, this pattern remains true. Very few asbestos cases go to trial and are instead concluded by settlement.

Since the days of the first asbestos exposure lawsuits, plaintiffs and defendants have been encouraged to settle and forego trial.

Settlement is seen as an attractive alternative to trial because asbestos exposure cases involve bringing into play numerous components which are typically very complex and require a great deal of skill to properly construct.

For example, it might not seem this way given how many decades asbestos exposure litigation has been around, but every case entails presentation of unique facts and contexts that need to be explored, picked apart, and weighed so as to establish whether a defendant can be held liable for the plaintiff’s injury—and, if liable, how much money it will take to fairly and adequately compensate the plaintiff for having his or her world turned upside down.

To help the jury make these determinations, each side will offer much evidence. Some of it will consist of testimony from medical and science experts. Gathering this evidence—which includes taking statements under oath from the parties and witnesses outside of court in advance of the trial date—can be a challenging process rife with pitfalls for inexperienced attorneys.

In light of these complexities and challenges, settlement is frequently seen as the preferred way to resolve asbestos exposure cases. Settlement allows the parties to much more efficiently address the claims and find an acceptable outcome.

While the sums a plaintiff receives at settlement may not be as high as that which could be won at the end of a full trial, history shows that settlement usually results in a very good outcome for plaintiffs.

First, settlement eliminates the risk of losing in court. Over the years, defendants have become adept at devising new ways to try to thwart claims at trial—especially those brought by plaintiffs represented by lawyers lacking asbestos-exposure lawsuit skills. A settlement signed by the defendant and accepted by the plaintiff is, on the other hand, a guaranteed favorable outcome.

Second, settlement can dramatically reduce the time it takes to go from injury to compensation. Some claims can be settled in a matter of a few weeks. Others take longer, but rarely as long as the runup to and the prosecution of a full trial. Many plaintiffs find it satisfying (and, in a large number of instances, a necessity) to receive compensation sooner rather than later.

Third, settlement can be less stressful on plaintiffs already struggling to bear up under the emotional strain of a serious medical condition and its attendant consequences. Knowing that it may not be necessary to go through a potentially lengthy trial process in order to resolve a claim has been known to elicit a huge sigh of relief from many a plaintiff.

Still, some plaintiffs find it more cathartic to not seek settlement and instead continue all the way through to trial. They have been injured—grievously so—as a result of what history suggests is corporate malfeasance for the sake of profits. And because of that, they want the fullest measure of justice they can possibly obtain.

So, they go forward to trial and hope for the best. Some plaintiffs have been substantially rewarded for their determination. By sticking it out and not settling, they went on to receive compensation ranging from as low as $1 million to a high of $20 million or more.

About the author…

Jason Steinmeyer is a seasoned trial attorney having joined The Gori Law Firm after an eight-year career as an Assistant Circuit Attorney in St. Louis where he tried over 80 jury trials.